Why modern “fast cars” look the part, make all the right noises, and quietly forgot what performance was ever for.

Introduction

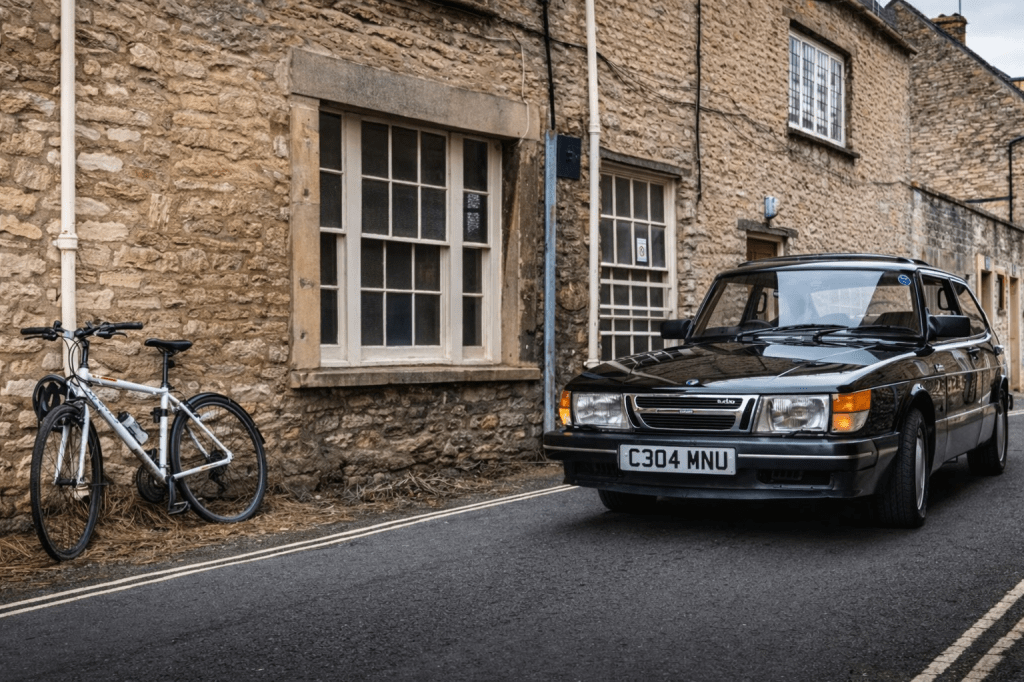

There was a time when the idea of a performance car required no explanation.

It was simply the fast one.

Not because it shouted about it. Not because it wore special badges or shouted through oversized exhausts. But because someone, somewhere inside the company, had taken a perfectly ordinary car and decided it should be better.

Lighter. Sharper. More responsive. Built around the unspoken assumption that the driver might actually care about how it felt to drive.

Today, that assumption has quietly disappeared.

We now live in an era where almost anything with a spoiler, dark wheels, and an aggressive name is marketed as “performance,” even if it weighs as much as a small moon and feels about as alert as a commuter train. Cars that look fast, sound fast, and are described as fast—yet leave you curiously unmoved once you’re behind the wheel.

This isn’t about one model or one brand. It’s about a shift in philosophy. A moment when the industry realised that performance could be sold far more effectively as theatre than as engineering.

And once you notice it, you start to see it everywhere.

Brand DNA vs the Concept

Performance brands didn’t become legends by accident. They earned their reputations the slow, expensive way—by building cars that were demonstrably better to drive than the standard versions they were based on.

BMW’s M cars weren’t subtle, but they were honest. They existed because engineers wanted sharper throttle response, firmer control, and a chassis that communicated rather than cushioned.

Audi’s RS models weren’t just faster in a straight line. They were more planted, more capable, and built with the assumption that speed needed control to be meaningful.

Mercedes-AMG, at its best, meant taking a sensible car and unapologetically turning it into something faintly unhinged—loud, muscular, and mechanically distinct.

In every case, the difference between the performance model and the standard one was physical. You could feel it. You could justify it.

Now those same names appear on cars whose primary upgrade is cosmetic confidence. Sport packages bolted onto fundamentally ordinary vehicles. SUVs wearing performance badges while retaining the driving manners of well-furnished living rooms.

The language hasn’t changed.

The meaning has.

Performance is no longer something the car does.

It’s something the car suggests.

Design Implications

The fake performance car is easy to identify, because it is designed from the outside in.

A real performance car begins with a difficult question:

What needs to be improved?

A fake one starts with a much easier one:

What needs to be seen?

So the industry delivers enormous wheels that compromise ride quality, exaggerated bodywork that serves no aerodynamic purpose, and vents that exist purely as visual punctuation. Rear windows shrink, sightlines disappear, and proportions grow heavier—because aggression sells better than balance.

Everything about the design implies urgency.

Almost nothing about it improves speed, control, or engagement.

It’s performance as costume.

A racing suit worn to sit still.

The irony is that genuinely useful design—the kind that improves cooling, reduces weight, or increases visibility—has become almost unfashionable. Practicality doesn’t photograph well. Substance doesn’t trend.

So it is quietly engineered out.

Interior Philosophy

This is where the transformation becomes impossible to ignore.

Once, the interior of a performance car was unapologetically focused. Supportive seats. Clear instruments. A steering wheel that felt mechanically honest. Everything arranged to remind you that the car existed for one reason: to be driven well.

Today, you are more likely to find yourself sitting high, peering over a swollen dashboard, surrounded by screens that simulate urgency while insulating you from the act itself.

The instruments are configurable but vague.

The steering is light but numb.

The driving modes change colours and soundtracks rather than fundamentals.

And when you accelerate, the noise you hear is often not the engine at all—but a carefully engineered impression of one, broadcast through the speakers to maintain the illusion.

This is not enhancement.

It is substitution.

A performance car should not need digital enthusiasm. If the mechanical experience were honest, it wouldn’t.

Market Positioning

The reason for all of this is neither mysterious nor ideological.

It is financial.

Performance—real performance—is expensive. It requires time, testing, specialised components, and a willingness to accept lower margins. Improving steering feel does not show up on a spreadsheet as neatly as a new trim package.

The appearance of performance, on the other hand, is remarkably cheap.

A badge.

Bigger wheels.

A sport exhaust, real or simulated.

These things allow manufacturers to charge significantly more for cars that behave almost identically to their standard counterparts. And because most buyers will never explore the limits of the chassis, the illusion holds.

Aspiration replaces ability.

Image replaces engineering.

And aspiration, it turns out, is far easier to monetise.

Brand Risk

Here is the uncomfortable truth the industry avoids.

If manufacturers genuinely committed to building real performance cars again—lighter, sharper, less compromised—they would immediately expose how hollow many of their current offerings are.

A properly engineered driver’s car would make “performance” SUVs look exactly what they are: styling exercises with inflated confidence.

It would force an awkward comparison between cars designed to be driven and cars designed to be bought.

That is not a conversation brands are eager to have with customers who have just financed the latter.

So instead, they dilute the definition of performance until it can comfortably include almost anything. In doing so, they protect margins, preserve egos, and quietly abandon the very standards that built their reputations in the first place.

Reality Check

- Could manufacturers still build real performance cars?

Of course. The platforms, powertrains, and expertise already exist.

- Would it make financial sense?

Only if they accepted that authenticity earns slightly less than illusion.

- Is there still an audience for them?

Yes. Enthusiasts didn’t disappear. They were simply outbid by customers who prefer the idea of performance to the discipline of it.

Final Verdict

The fake performance car did not emerge because drivers stopped caring.

It emerged because the industry discovered that excitement could be simulated more profitably than it could be engineered.

So now we are surrounded by cars that look fast, sound fast, and are marketed as fast—yet rarely feel as though they were designed with driving as the priority.

That is the difference between performance as a marketing concept and performance as a mechanical truth.

And until buyers begin rewarding the latter over the former, the outcome is inevitable.

The fake performance car exists for one reason.

Because it sells better than the real one.

Leave a comment