A speculative look at why modern vehicles have become larger, heavier, and somehow less usable for the people actually sitting in them.

Introduction

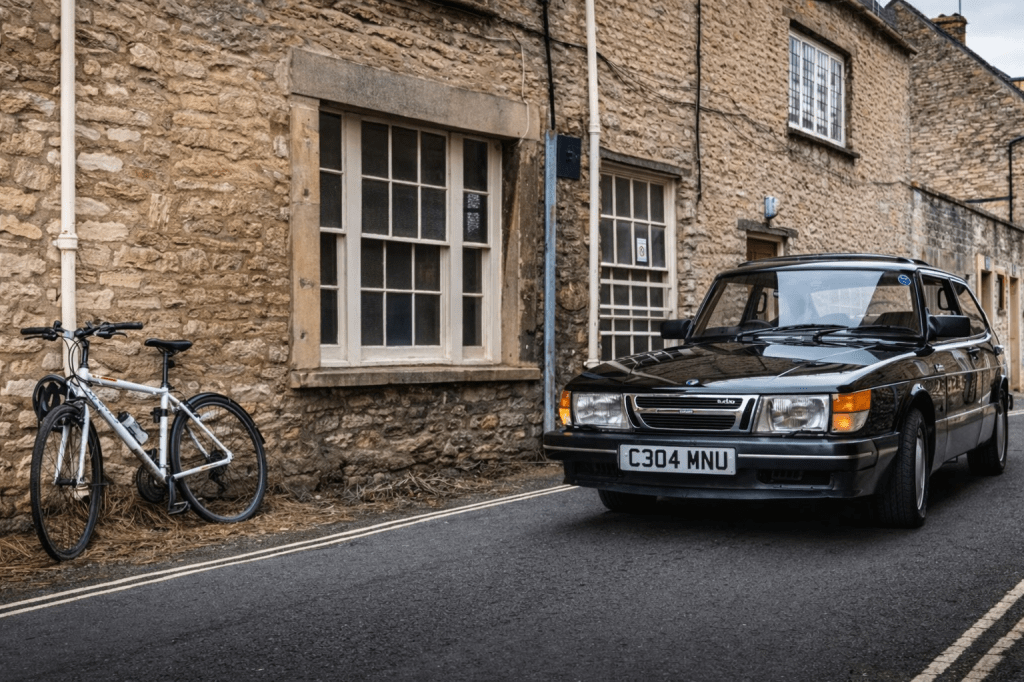

This vehicle does not exist, but the problem it represents is everywhere.

It’s appearing online because the modern car market has drifted so far from practical packaging that even hypothetical “fixes” now feel plausible.

The conflict is simple: cars have grown dramatically on the outside, while the experience inside has become cramped, compromised, and often uncomfortable.

This is not a styling quirk or an engineering accident.

It is the inevitable outcome of how modern platforms are designed, marketed, and sold.

And it has left us with cars that are visually imposing yet fundamentally miserable for daily use.

Brand DNA vs the Concept of “Big Means Spacious”

Historically, size implied comfort.

A Mercedes S-Class was enormous because it was supposed to feel like a rolling lounge.

A Land Cruiser was large because it had to carry people and equipment across continents.

Modern brands have kept the exterior size, but quietly abandoned the interior logic.

A compact SUV now has the road presence of an executive saloon, yet offers rear legroom closer to a supermini.

An electric “family car” looks vast, but its battery pack forces passengers into a high, knees-up seating position that nobody would voluntarily choose.

This is a betrayal of brand DNA.

When a car looks large but feels small inside, it has failed at its most basic promise.

The current industry approach treats interior space as secondary to visual impact.

Conclusion: Modern car design has inverted priorities — it values exterior scale over interior usability, undermining the very reason these vehicles exist.

Design Implications: How Packaging Was Sacrificed for Aesthetics

The design departments are responsible for most of the damage.

Modern vehicles use oversized wheels and thick structural elements to achieve a “premium” stance.

That decision alone consumes valuable cabin width and pushes the floor higher than it needs to be.

Then comes the rising beltline.

It creates a sleek, aggressive silhouette on the outside.

Inside, it reduces glass area and shoulder room, leaving passengers feeling like they’re travelling in a fortified box.

Rooflines have also become dramatically lower.

Manufacturers want SUVs that look like coupés, so they simply cut headroom to achieve it.

The result is a tall vehicle you cannot stand upright in.

Aerodynamics and crash regulations are often used as justification.

In reality, most of this lost space is the cost of styling decisions, not safety ones.

Conclusion: The current design philosophy deliberately reduces interior space to satisfy visual and aerodynamic targets, prioritising appearance over comfort.

Interior Philosophy: The Era of the Bulky Cabin

Interior design has followed the same path.

Older dashboards were thin and upright.

They left space for the occupants.

Modern dashboards are thick, layered, and aggressively sculpted.

They dominate the front of the cabin and eat into knee room that used to belong to the driver and passenger.

Centre consoles have expanded in the same way.

Where a small tunnel once existed, we now get a full-width “command centre” packed with screens, buttons, and unnecessary bulk.

It looks expensive. It feels intrusive.

Seats have become larger as well, but not more comfortable.

They are thicker, higher, and more complex, leaving less room for rear passengers while offering no meaningful improvement in ergonomics.

The overall effect is unmistakable.

You are not sitting in a spacious cabin.

You are sitting in an enclosed structure designed to look luxurious.

Conclusion: Modern interiors are designed for visual theatre rather than occupant comfort, sacrificing usable space to create the illusion of sophistication.

Market Positioning: Why This Keeps Happening

This problem persists because it makes commercial sense.

Manufacturers have learned that customers respond to vehicles that appear substantial.

The taller and wider the car looks, the more it can be sold for.

Interior space, by contrast, does not photograph particularly well.

So it is treated as optional.

The customer who needs more room is simply encouraged to move to the next model up the range.

A slightly larger SUV is always waiting, with a slightly higher price tag.

This creates a predictable staircase of upsizing.

Buyers are moved upward in cost and footprint without actually gaining meaningful interior comfort until they reach the top of the brand’s range.

At that point, they are essentially purchasing a luxury product to solve what should have been a packaging issue.

Conclusion: The industry maintains cramped interiors because it encourages profitable model upsizing, not because it cannot build better-packaged cars.

Brand Risk: What This Means for the Manufacturers

This trend is not sustainable for brands that claim to value practicality and engineering.

A large, uncomfortable vehicle damages trust.

It creates the impression that the manufacturer is more interested in style and margins than in solving real-world problems for the customer.

This is especially risky for brands built on usability.

If Land Rover sells an SUV that is no more spacious inside than a Volkswagen Golf, it loses credibility.

If Volvo sells a family crossover that struggles to fit a family, its entire positioning collapses.

Premium brands are slightly more insulated, but not immune.

When a £70,000 electric saloon has less rear space than a £25,000 estate car from a decade ago, the customer notices.

And they remember.

Conclusion: Brands that continue inflating vehicle size while shrinking interior usability erode their identity and risk long-term customer loyalty.

Potential Specifications

If manufacturers wanted to correct this, the technical solution is straightforward.

They simply have to prioritise space rather than appearance.

- Powertrain (with reasoning)

A compact hybrid or EV drivetrain designed to minimise cabin intrusion. Current small EV platforms already allow this when packaging is treated as a priority.

- Power output (with context)

Between 180–300hp. Adequate for family and executive vehicles without requiring oversized cooling or structural reinforcement that reduces cabin room.

- Drivetrain

Primarily front-wheel drive or dual-motor all-wheel drive for stability. The goal is efficient packaging, not performance theatrics.

- Platform

A modular architecture focused on maximising wheelbase and interior volume within a restrained exterior footprint.

- Performance estimates

0–60mph in 7–9 seconds. This is a usability-focused vehicle, not a marketing statement.

- Estimated price range

£30,000–£50,000. Realistic for a well-packaged, space-efficient modern car built using current technology.

Reality Check

- Could this be built?

Yes. The platforms and powertrains already exist. The issue is not capability; it is priority.

- Would it make financial sense?

Only if manufacturers accept lower margins. At present, selling visually larger cars is more profitable than selling more spacious ones.

- Is there a realistic customer?

Yes. Buyers want comfort, practicality, and honest packaging. The market simply isn’t giving it to them at sensible price points.

Final Verdict

Modern cars have become larger and more visually aggressive while offering less real interior comfort and usability. This is not innovation. It is the deliberate result of styling-led design, platform cost management, and profit-driven upsizing. The exterior has been inflated for marketing; the interior has been compromised for margins.

Cars are supposed to serve the people inside them.

Right now, they don’t.

Leave a comment